By Tracey Cumming, Senior Technical Advisor, BIOFIN

Nations from around the world will meet in December in Montreal, Canada, for part two of the CBD COP15 – the 15th Meeting of the Parties of the Convention of Biological Diversity. This COP has a particularly daunting task: To make up for the previous decade of missed targets and to agree on a new framework and targets to be reached by 2030.

The strategy for the next decade called the ‘Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework’ and its targets need to put the world back on track towards the CBD’s 2050 Vision of a world of “Living in harmony with nature” where, by 2050, biodiversity is valued, conserved, restored and wisely used, maintaining ecosystem services, sustaining a healthy planet and delivering benefits essential for all people.We are far from achieving this vision.

Nature loss poses a grave risk to the global economy and societies.

Loss of ecosystem services could depress annual global GDP by up to $2.7 trillion by 2030, with a greater impact in low-income and lower middle-income countries. Nature has declined more extensively over the past 50 years than at any other time in human history. Along with climate change, biodiversity loss is now a profound threat facing humanity.

Nature is humanity’s most powerful asset to achieve a sustainable, thriving, flourishing future.

Nature-based solutions comprise over one-third of our most cost-effective solutions to climate catastrophe – reducing flood risk and watershed protection, improving crop yields and forest products, and potentially sequestering up to 1.7 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent annually.

Negotiations for the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework have not been smooth, with few targets being agreed upon to date. While there are strong calls for an ambitious framework, including from the business and finance sector, much of the text of the draft Post 2020 Global Biodiversity Framework is still “bracketed” – indicating a lack of consensus with more negotiations to come in Montreal.

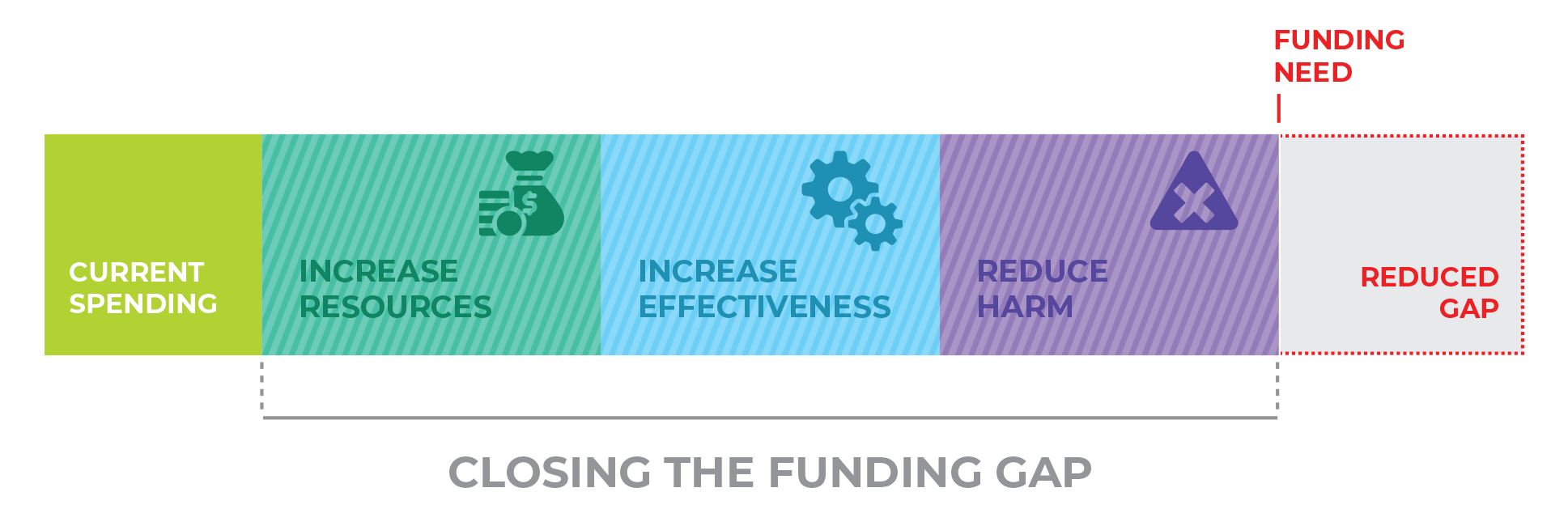

One of the main reasons many of the previous decade’s biodiversity Targets were not reached was insufficient resources to match the need. We call this the ‘funding gap’. In the draft Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework, targets related to closing the funding gap are among those under intense debate.

What is the biodiversity funding gap?

It is difficult to measure the global biodiversity funding gap accurately. There have been several estimates using different methodologies and considering different targets.

For example, the funding gap for safeguarding 30 per cent of our terrestrial and marine areas has been estimated to be between $103 billion and $178 billion annually (around 0,3% of our global GDP). The funding gap for the broader range of actions under the CBD has been estimated to be between $599 billion and $824 billion annually.

While there remains some uncertainty about the exact size of the funding gap, there are three things we do know:

-

The funding gap and its impact on nature are too large to ignore.

-

The funding gap is only a small fraction of global GDP – around 0,7%. If the world is serious about closing the funding gap, it is entirely possible.

-

The actions required to reduce the gap are wide-ranging and include efforts across all of society.

Three actions for closing the funding gap

Closing the biodiversity funding gap will require actions on three fronts:

- Increasing and catalysing resources

- Reducing harmful investments to reduce the total funding needs

- Improving the effectiveness and efficiency of our actions – doing more with our limited resources

1. Increase and catalyse resources

There must be an increase in financial resources committed to rebalancing nature with people. Funding will be needed from all sources – public and private sector, domestic and international.

Most of the world’s biodiversity exists in countries that require financial support to achieve biodiversity goals and targets, and effective, accessible and catalytic ODA will need to be scaled up for these countries. With 80 – 85% of the biodiversity funding coming from domestic budgets, this will need to continue to be a major source of sustained funding.

Governments also play an important role in catalysing crucial private sector investment through a range of policies and mechanisms, such as early-stage grants, blended finance, and fiscal incentives to reward biodiversity-positive investments.

|

2. Reduce harm

Economic development does not need to come at the cost of the environment. Far more money is spent causing harm to nature than is spent safeguarding and restoring it.

We gradually eat up our natural capital at the cost of short-term economic growth, instead of leaving it intact for future generations. One way to reduce the funding gap is to cause less harm, resulting in a lower funding need for reversing the damage to nature. Reducing the negative impact caused by existing actions eases the strain on funding needs.

A major driver of harmful expenditure are subsidies inadvertently causing harm to biodiversity. Subsidy repurposing is one of the biggest opportunities to close the funding gap globally.

Nearly $542 billion is spent yearly on agricultural, fisheries, and forestry subsidies that degrade nature. In agriculture, support for practices harmful to both nature and health need to be repurposed to achieve healthy, sustainable, equitable and efficient food systems that are nature positive. BIOFIN is working to identify and help repurpose potentially harmful subsidies at country level, focussing on the most impactful sectors in each country.

Reducing negative impacts is not only about redesigning harmful subsidies. Our economic system currently does not take nature into account, resulting in a continued loss of nature, and an increasing cost to restore and reduce pressures on nature. This market failure needs to be addressed with a range of tools. These include: better regulation to safeguard nature, economic incentives to reward nature positive behaviour; getting the prices right by identifying, measuring and capturing the effects on nature into market transactions; and providing more transparency to consumers so that they can make informed choices on the products and services they consume.

Reducing negative impacts helps us to avoid or reduce future costs, but we still need more resources to bring nature and people back into balance.

3. Enhance effectiveness and efficiency

Enhancing effectiveness and efficiency is about how we do things better. While critically important, is often overlooked as a priority.

Countries need to do more with the limited resources we currently have. This includes building capacity so that financial resources are spent wisely, creating partnerships to enable more impactful outcomes in complex systems, better and more result oriented planning and budgeting which takes nature and it’s values into account, and rethinking how different institutions work together more effectively.

Systemic change across all of society

Reducing the funding gap will not be easy. It requires transformational shifts in governance, financial and economic systems, with actions required by the public sector, business, the finance sector and society as a whole.

Businesses and the finance sector have called for governments to change the rules of the game: to create a legal and policy framework to enable them to better align financial flows with a nature-positive objective.

How can the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework Targets help close the funding gap?

The draft Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework includes five targets that tackle different aspects of closing the funding gap.

.png)

National Biodiversity Finance Plans and BIOFIN helping to close the funding gap

One of the first steps countries can do is develop national biodiversity finance plans to guide how to close the funding gap by addressing the drivers of biodiversity loss, improving effectiveness, and increasing the resources available for achieving the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework.

This can be done in tandem with a revision of country National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans and taking into account nature-based solutions for addressing the climate-change crisis.

BIOFIN has been working with countries worldwide to develop biodiversity finance plans and deliver solutions to closing the funding gap. Through new legislation, biodiversity safeguards, and market-based tools, transformational change to reduce the funding gap is already happening. Ambitious targets in the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework will pave the way for the nature-positive future that we need. This year the world has the opportunity to commit to goals that will secure the health and wellbeing of people and the planet.

Photos courtesy of Unsplash: (c) Annie Spratt, (c) Holly Mandarich, (c) Abigail Keenan, (c) Vincent van Zalinge

Categories

Archives

- May 2025 (4)

- April 2025 (9)

- March 2025 (8)

- February 2025 (2)

- January 2025 (5)

- December 2024 (4)

- November 2024 (5)

- October 2024 (14)

- September 2024 (6)

- August 2024 (9)