Nature conservation can be a challenge, especially for local governments. Protected areas can reap tremendous benefits for a country, and indeed the planet. But often local governments must deal with a double bind of having to shoulder the costs of conserving the land and water as well as the costs of not being able to develop the land for agriculture or industry, for example.

However, the growing popularity of ‘ecological fiscal transfers’ – EFT – is proving to be a transformative way to lift the burden off the shoulders of local governments and to easily channel funds for conservation.

A new study published in the Journal Nature Sustainability, co-authored by BIOFIN, has shed light on how the EFT finance mechanism is being used to transfer public funds from national or sub-national governments that reap the benefits of conservation in a country to the local governments where the conservation is taking place.

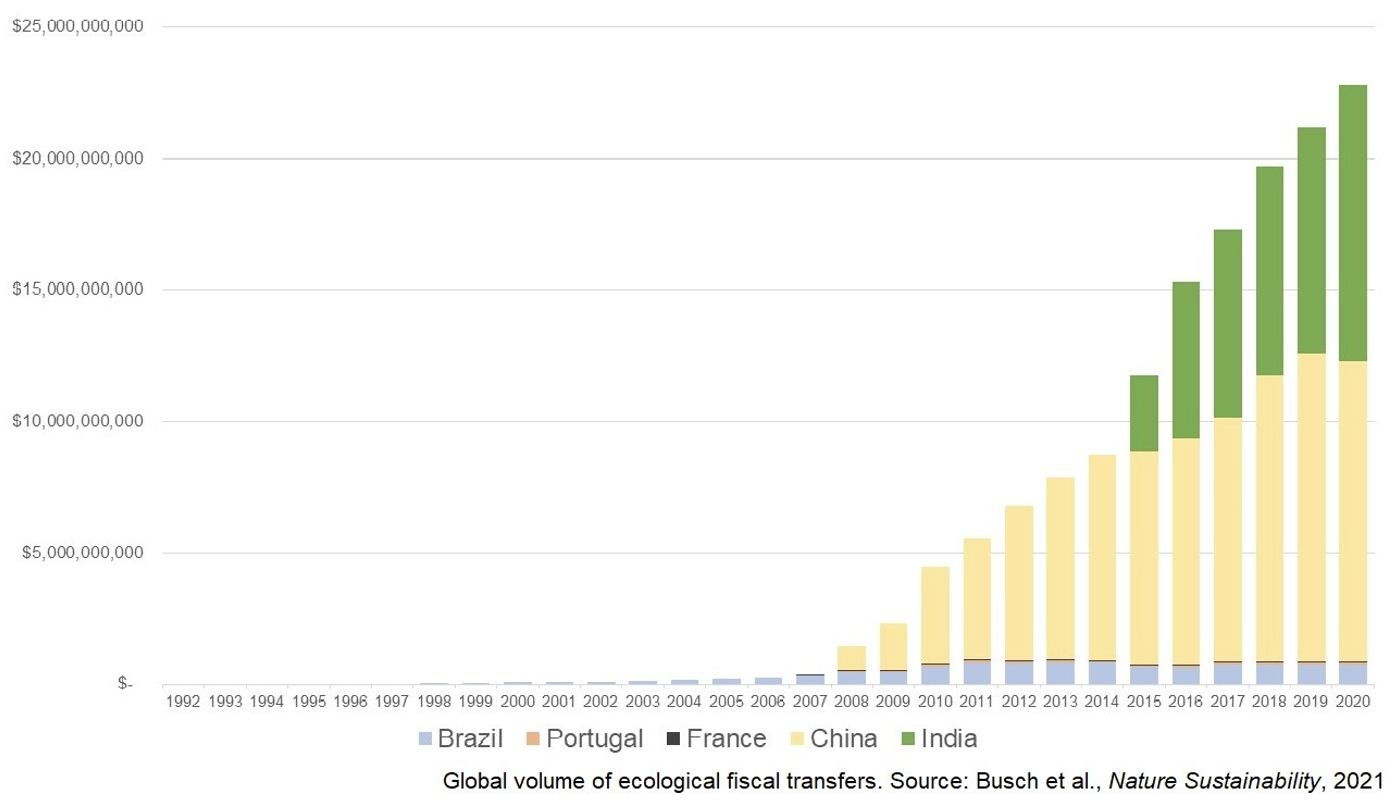

The study reveals that around US$23 billion per year is being used in EFT, and it is growing rapidly with many countries exploring this concept. While they started as a way to compensate for conservation-related losses, they are now being used to incentivize nature protection efforts.

Case studies

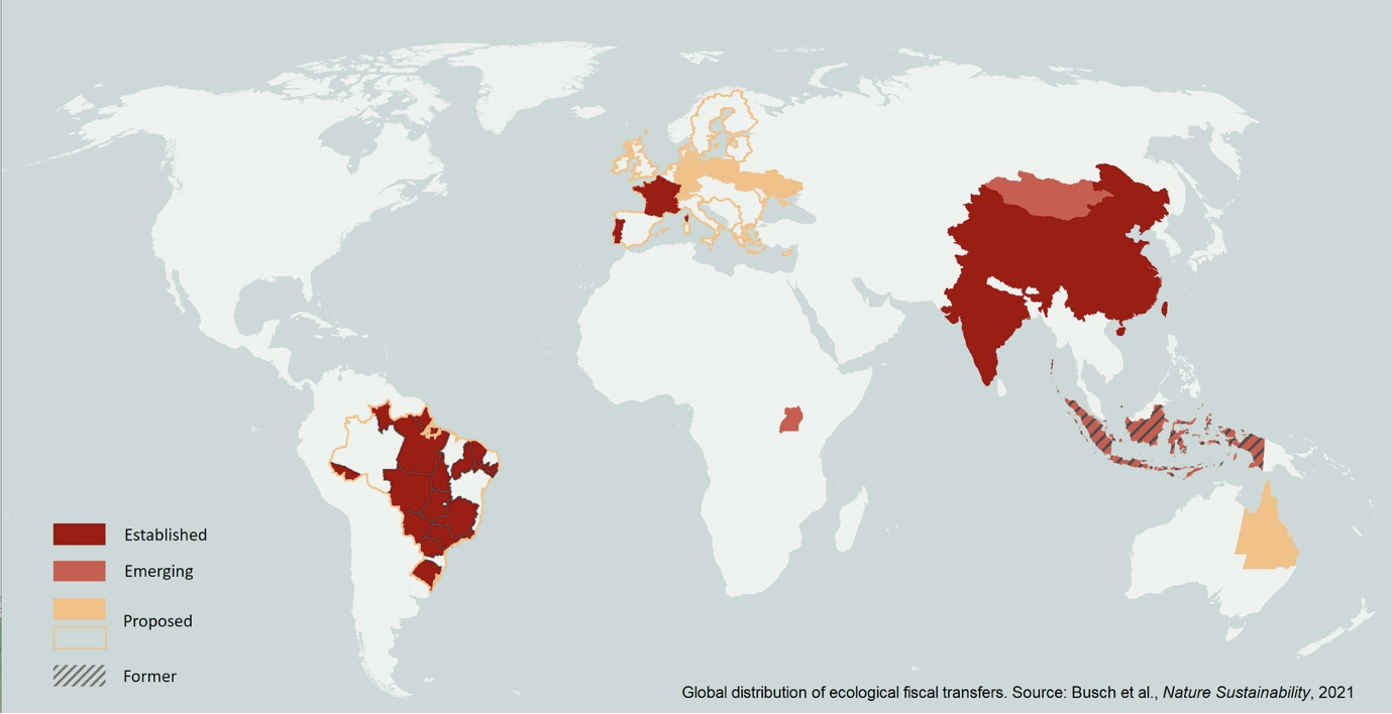

The study delves into the five countries that have established EFT. While literature previously existed looking at individual countries, few saw the far-reaching potential EFTs could bring to countries across the world.

Brazil is among the most-studied countries, with 18 states transferring funds to local governments. In India, around US$6-11 billion per year of transfers have been sent to states based on forest cover in 2015. China has also been running EFT for over a decade, and France and Portugal have also transferred money to local governments based on conservation efforts.

In total, it was found that 15 countries had, have or are proposing EFT.

Diverse & flexible

What is striking about EFT is how diverse they can be.

In Indonesia, regional fiscal transfers have been in action since around 1998. The Reforestation Fund transfers national revenues to provincial and district levels based on ecological indicators in the form of special allocation funds. Today, BIOFIN is working with provincial and district authorities to see how these transfers can go one step further and reach government at village level.

“This isn’t about finding extra money, it’s about finding additional indicators to reward the local governments and, we hope, to continue protect and restore nature,” said Bayuni Shantiko, BIOFIN Indonesia National Coordinator.

“At the moment discussions are underway to see if this can also be used at village-level. For example, if a village has developed a reforestation plan or water catchment improvements, there could be ways to receive additional funds from the district level without costing the district anything more.”

In Malaysia, BIOFIN has been strongly promoting EFT. Intergovernmental fiscal transfer schemes from federal government to States are common in Malaysia but these schemes do not include environmental criteria or indicators.

Drawing on lessons from BIOFIN’s early work in the country, a GEF-funded project titled ‘Enhancing Effectiveness in Financial Sustainability of Protected Area in Malaysia’, UNDP prepared a policy paper on EFT indicating opportunities and way forward for its application in the country that led to the budget allocation of around US$16.5 million in years 2019 and 2021 for the protection and restoration of biodiversity.

“The EFT in Malaysia, although in its very early stage of design, can be the game changing solution for incentivizing the States in Malaysia to protect and conserve nature, in the right mix of fiscal incentives,” said Pek Chuan Gan, Programme Manager at UNDP Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei Darussalam.

“There is a notable policy shift and recognition that there are costs incurred by the States for environmental preservation and that there is a fiscal responsibility despite the decentralisation on environmental matters. To make them function, we need a strong policy and legal instrument as well as a robust institutional framework across different levels of governance in the country. Also, this cannot be done in a silo – it required a whole-of-government approach to design an EFT with a robust environmental criterion to determine budget allocations.”

A rapid rise

As mentioned previously, the growth of EFT has been rapid, rising from US$300 million a year to US$23 billion today.

This growth is very likely to continue as they offer governments relatively simple means to transfer existing funds to local governments to support the protection and restoration of nature through the reformulation of existing revenues. As the funds are already existing, it means they do not need to raise additional tax revenues or ask for new funding.

"There’s a timeliness to this. It's a big year for the climate and biodiversity, with countries set to pledge new goals to protect nature and tackle global warming later this year. At the same time, budgets are tight — especially with COVID — and EFTs are a way to do something green with big dollars without raising taxes or taking money away from something else. It’s the right idea at the right time," said lead author Jonah Busch, Climate Economics Fellow at Conservation International.

There are also promising signs that EFTs will continue to flourish across the world.

"I was surprised to see how large and rapidly growing EFTs are. The more we looked, the more countries we found where they are becoming part of the conversation. And even after the paper was submitted, we started to hear more countries expressing interest in this concept," continued Busch.

At a time when public expenditures have been stretched thin by the COVID-19 pandemic, and ahead of the upcoming COP for Convention on Biological Diversity in China, greening a small fraction of the US$5 trillion transferred to local governments would be a massive boon for investing in nature.

Categories

Archives

- April 2025 (9)

- March 2025 (8)

- February 2025 (2)

- January 2025 (5)

- December 2024 (4)

- November 2024 (5)

- October 2024 (14)

- September 2024 (6)

- August 2024 (9)

- July 2024 (7)